Prophecy

In our modern world, we often view prophecy through a lens of skepticism, seeing it as vague predictions or moralizing stories that feel distant from our daily lives. We might skim these ancient texts for clues about the end times or dismiss them as irrelevant relics. But picture yourself in the ancient Near East, where empires rose and fell, kings wielded unchecked power, and ordinary people faced injustice, war, and spiritual drift. Into this turmoil, God sent prophets -- not mere fortune-tellers, but courageous voices who spoke His truth with unflinching conviction.

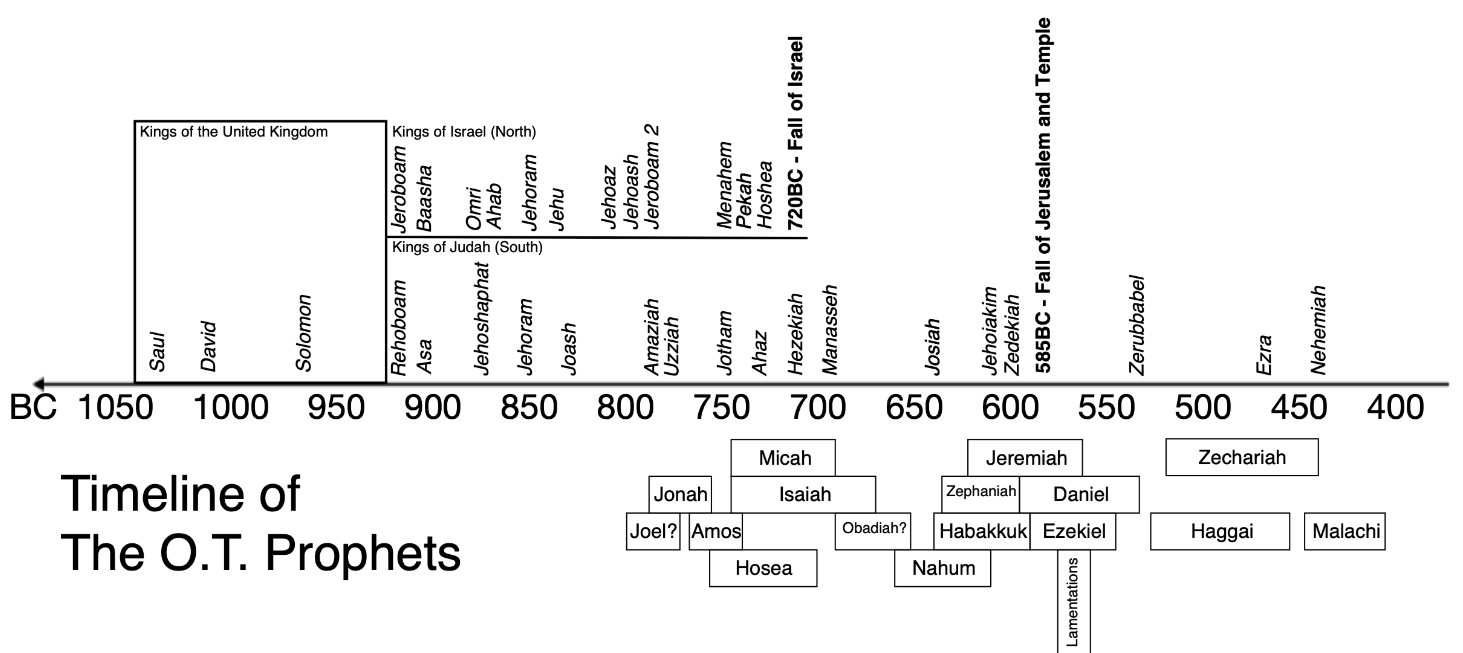

These prophets challenged kings, exposed societal sins, and wove visions of hope that pierced through despair. The Old Testament prophets, active from roughly the 8th to 5th centuries BC, crafted a divine narrative of judgment, mercy, and redemption, organized into the Major Prophets -- Isaiah, Jeremiah (with Lamentations), Ezekiel, and Daniel -- and the Book of the Twelve, often called the Minor Prophets for their brevity (not their impact). Their messages transcended their era, pointing to Christ and challenging us today to confront our own rebellions and repent.

Prophets in the Bible were God’s chosen messengers, tasked with holding His people accountable to its covenant. As the nation veered into idolatry, oppressed the vulnerable, or sought security in foreign alliances, prophets like Amos thundered against exploitation, while Isaiah painted portraits of a Messiah who would restore all things.

Their words blended immediate warnings -- addressing crises like Assyrian invasions or Babylonian exile -- with long-term hope, envisioning a “day of the Lord” that brought both judgment and salvation. This layered perspective makes their writings timeless, diagnosing humanity’s recurring failures while pointing to divine rescue. Their courage in crisis -- speaking truth to power, often at great personal cost -- challenges us to reflect: If these prophets confronted the injustices of their day, what would they say about our world’s inequalities, moral relativism, and spiritual apathy?

Their voices travel across time and urge us to examine our lives and societies, seeking alignment with God’s justice and mercy.

Major Prophets¶

The Major Prophets -- Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel -- offer sweeping narratives that weave together personal stories, vivid visions, and divine oracles. Their longer books tackle Israel’s unfaithfulness, the agony of exile, and the promise of restoration. Through lives marked by suffering and obedience, these prophets modeled what it means to deliver God’s message, even when it led to rejection or death. Their words span centuries, from Judah’s pre-exile struggles to the Babylonian captivity, providing a comprehensive view of God’s dealings with His people. As we explore their messages, we’re invited to ponder how their calls to repentance and hope resonate in our own era of uncertainty and division.

Isaiah¶

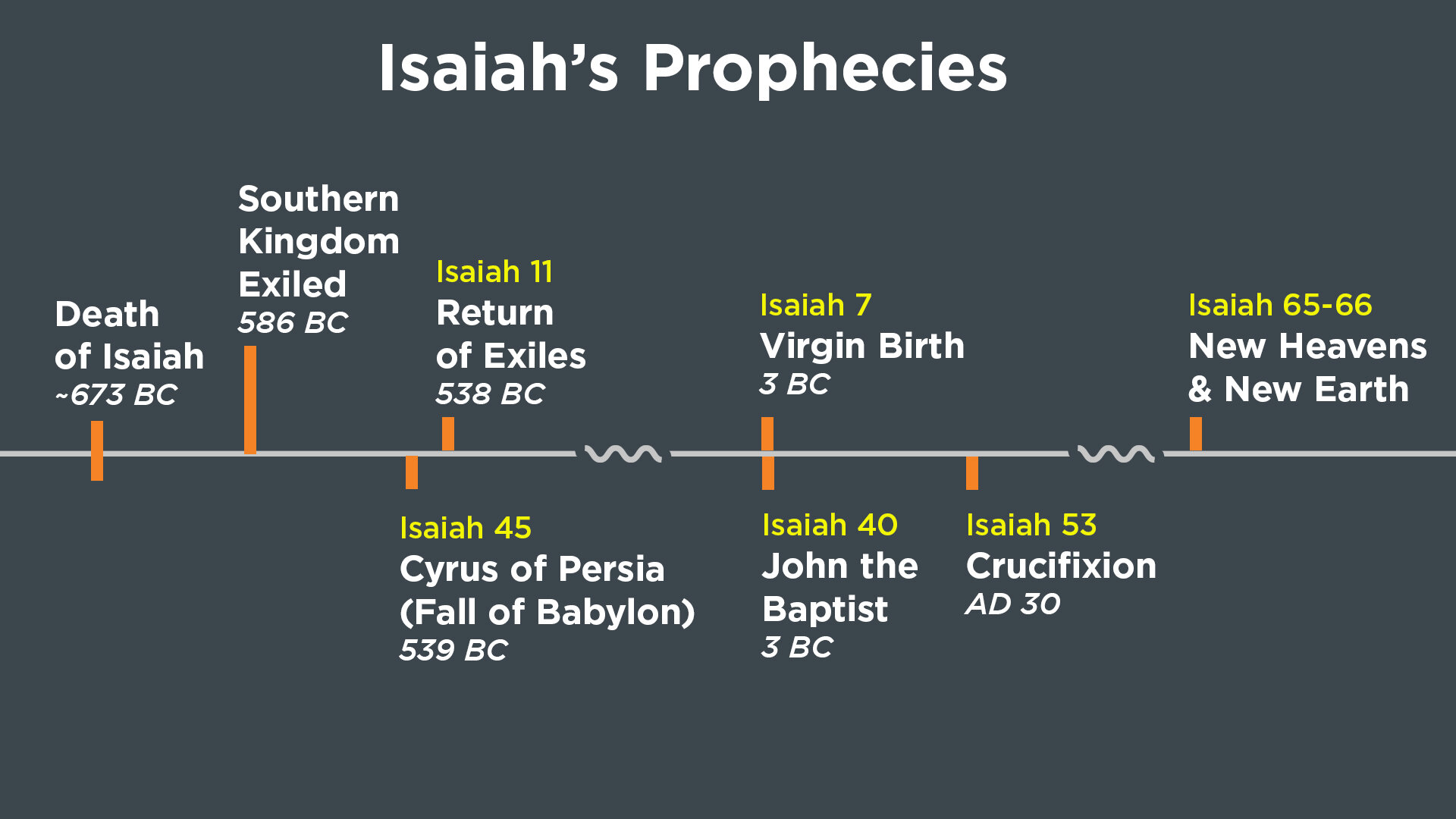

Isaiah ministered in Judah from approximately 739 to 701 BC, a period of political upheaval as the Assyrian empire loomed and internal corruption eroded the nation’s moral core. Serving under kings like Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, he urged reliance on God over fragile alliances with foreign powers. His 66-chapter book, often called the “fifth Gospel,” is a masterpiece of prophetic literature, blending judgment, mercy, and Messianic hope with such clarity that St. Jerome described Isaiah as an evangelist, not merely a prophet. The book’s structure mirrors the Bible itself: chapters 1–39 focus on rebuke and judgment, akin to the Old Testament, while chapters 40–66 emphasize comfort and redemption, echoing the New Testament’s promise. However, these chapter divisions, added by medieval Christians in the 13th century, should not dictate interpretation; the book demands to be read as a unified whole, its themes spiraling across time -- from Isaiah’s day to the exile, the Messianic age, and the end of history.

At its heart, Isaiah’s narrative confronts humanity’s persistent rebellion against God, the just consequences that follow, and the boundless mercy that culminates in the Messiah. It’s a story of cycles: God nurtures His people like children, yet they turn to idols, face punishment, and receive restoration through grace. This pattern, vivid in Isaiah’s time, persists today, prompting us to ask: How do we repeat Israel’s errors, chasing modern idols like wealth, status, or self-reliance?

Commission¶

Isaiah’s prophetic calling began with a transformative vision in the year King Uzziah died (c. 740 BC), when he beheld the Lord enthroned, His robe filling the temple, surrounded by seraphim chanting, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of His glory” (Isaiah 6:1–3). The temple shook, smoke rose, and Isaiah, struck by his own sinfulness, cried, “Woe is me! for I am undone; because I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips” (6:5). A seraph touched his mouth with a live coal from the altar, purging his sin, and when God asked, “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” Isaiah responded, “Here am I; send me” (6:8). This encounter reveals the pre-incarnate Christ, the Word of God, and the coal foreshadows the Eucharist, where Christ’s body cleanses believers. In Orthodox liturgy, priests echo the seraph’s words post-Communion: “Behold, this hath touched thy lips, and taketh away all thine iniquities and purgeth all thy sins.”

This vision sets the tone for Isaiah’s mission: a humbling encounter with divine holiness that purifies and commissions. It invites us to consider our own “unclean lips” -- how often do our words or actions reflect impurity? The coal’s cleansing points to Christ’s atonement, showing that true prophecy begins with personal transformation. Isaiah’s willingness to serve, despite knowing the cost, challenges us to embrace God’s call, even when it leads to sacrifice.

Despite his faithfulness, Isaiah’s truth-telling provoked hostility. Jewish tradition, echoed in Hebrews 11:37, records that he was martyred under King Manasseh, sawn in half for his bold proclamations. His life forces us to reflect on the cost of speaking truth in a world that often resists it. In an age of cancel culture and moral compromise, Isaiah’s courage asks: Are we willing to stand for truth, even at personal cost?

Old Covenant¶

Isaiah’s prophecies are deeply rooted in the old covenant, the sacred relationship between God and Israel established through Abraham and Moses. This covenant promised blessing for obedience but judgment for rebellion, and Isaiah vividly depicts Israel’s failure to uphold it. God laments, “I have nourished and brought up children, and they have rebelled against me” (1:2). The nation’s sins -- idolatry, injustice, corrupt leadership -- are laid bare, with warnings of “childish princes” and “babes” ruling, leading to oppression and chaos (3:4–5). These critiques resonate eerily with modern dysfunctions, where leaders prioritize power over wisdom, and societies fracture under greed and division.

Yet, judgment is never God’s final word. Isaiah repeatedly calls Israel to turn from idols -- man-made gods of silver, gold, or ideology -- to the true Creator who “formed thee from the womb” (44:24). Promises of mercy shine through: “I will pour water upon him that is thirsty, and floods upon the dry ground: I will pour my spirit upon thy seed” (44:3). This cycle of rebellion, consequence, and restoration mirrors humanity’s story, showing why we need a Redeemer beyond human effort. It’s a sobering lesson: God’s justice corrects, but His mercy invites return. In our own lives, what idols -- whether materialism, technology, or self -- leave us spiritually parched, thirsting for the Spirit’s refreshment?

New Covenant¶

Isaiah’s prophecies transcend the old covenant, laying the foundation for the new covenant fulfilled in Christ. His Messianic visions are stunningly precise, painting a Savior who is both divine and human. The promise of a virgin conceiving Immanuel, “God with us” (7:14), finds fulfillment in Mary and Jesus (Matthew 1:22–23). The child born as “Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace” (9:6–7) will rule eternally on David’s throne, establishing justice forever. From Jesse’s root (David’s father), a Branch grows, anointed with wisdom and might (11:1–2), a righteous King who transforms the world (32).

From chapter 40, the tone shifts to comfort: “Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God” (40:1), heralding the end of exile and the coming of John the Baptist, the “voice crying in the wilderness” (40:3). Idols are mocked as powerless (44), contrasted with the Redeemer in whom God delights (42:1). A Trinitarian glimpse appears: “The Lord God, and his Spirit, hath sent me” (48:16). Salvation is no mere concept but a person -- the Word of God -- who overcomes death (46:10–13).

Babylon’s fall (47) exposes false saviors like astrologers, while the Suffering Servant (50–55) bears humanity’s sins, “wounded for our transgressions” (53:5), offering His back to smiters (50:6). This Servant, speaking with authority and often in past tense (51:6), is the pre-incarnate Logos, God Himself. The coal’s purging (6:6–7) echoes the smith’s fire crafting redemption (54:16), culminating in an everlasting covenant of peace (55) open to all.

These prophecies expand God’s plan: salvation for Gentiles (49:6), light to nations. Isaiah’s vision challenges us to move beyond narrow loyalties or prejudices, embracing Christ’s universal call to salvation. In a world divided by tribe and ideology, how do we respond to a Savior who redeems all nations?

Final Judgment¶

Isaiah’s eschatology weaves a vivid tapestry of judgment and renewal, with local events foreshadowing the ultimate “day of the Lord.” Chapter 13 depicts Babylon’s fall as a type of end-times collapse, with cosmic upheaval -- stars darkening, earth shaking -- echoed in Revelation. Chapter 14 mocks Babylon’s king, often seen as Satan cast into the pit (14:12–15), a humiliating end for prideful powers. Assyria and Philistia face similar fates (14), showing no nation escapes God’s justice.

Chapter 24 paints a global judgment: cities desolate, joy turned to mourning as God shakes creation’s foundations. Yet, chapter 25 bursts into praise, with God swallowing death forever, wiping tears, and hosting a banquet for all peoples. Chapter 26 sings of a salvation city, its gates open to the righteous, while chapter 27 celebrates slaying Leviathan, the chaotic serpent, signaling victory over disorder.

Chapters 32–33 exalt God in consuming fire, toppling Satan and forgiving Zion. Chapter 57 notes the merciful spared from evil, while the wicked, trusting idols, find no peace. Chapter 58 teaches fasting that pleases God -- loosing bonds of injustice, sharing bread -- and honoring the Sabbath for delight in the Lord. Chapter 59 explains sin’s darkness hides God’s face, yet the Redeemer comes for the repentant. Chapter 63’s vengeance day, with the Lord treading the winepress alone, blood-stained (echoed in Revelation 19:15), underscores divine justice.

These fractal patterns -- local judgments prefiguring the ultimate -- reveal history’s divine design. In our era of systemic corruption and global crises, Isaiah’s warnings urge us to repent before the day arrives, while his promises of mercy invite us to trust in God’s redemptive plan.

New Heaven¶

Isaiah’s vision culminates in a new creation, offering hope that transcends judgment. Chapter 60 envisions a kingdom of salvation and praise: no sun or moon, only the Lord as everlasting light (60:19–22). Mourning ends, the righteous inherit the land, and a small nation grows mighty. Chapter 61 proclaims an everlasting covenant, with righteousness shining before nations. Chapter 62 promises a new name (62:2; cf. Matthew 1:21 for Jesus), signaling salvation’s dawn.

Chapter 64 cries for heavens to rend and God to descend, while chapter 65 blends grace and judgment: a new heaven and earth where wolf and lamb feed together, lion eats straw, and the serpent’s food is dust (65:25) -- peace restored, chaos subdued. Chapter 66 contrasts those choosing God’s delight with those facing judgment, culminating in a male child from Zion and all flesh worshiping (66:23).

No human intercessor suffices (60); the Suffering Servant, the divine Logos, brings redemption. If creation groans for renewal, Isaiah’s vision inspires us to live for the new heaven and earth, where God’s presence banishes sorrow.

Authorship¶

The question of Isaiah’s authorship has sparked significant debate, particularly among modern scholars who propose multiple writers. The “Deutero-Isaiah” theory suggests chapters 1–39 come from the 8th-century prophet, while 40–55 (or 40–66) were penned by an anonymous figure during the Babylonian exile, and the “Trito-Isaiah” hypothesis posits chapters 56–66 as the work of a post-exilic author. These ideas stem from perceived shifts in style, tone, and historical context, with later chapters seemingly addressing exilic audiences directly.

However, these theories lack concrete evidence and clash with both scripture and ancient tradition. The Gospel of John explicitly attributes passages from both Isaiah 6 (the commission vision) and Isaiah 53 (the Suffering Servant) to a single prophet, Isaiah, connecting them with the phrase “because Isaiah said again” (John 12:37–41).

John 12:37-41

But though he had done so many miracles before them, yet they believed not on him: That the saying of Esaias the prophet might be fulfilled, which he spake, Lord, who hath believed our report? and to whom hath the arm of the Lord been revealed? Therefore they could not believe, because that Esaias said again, He hath blinded their eyes, and hardened their heart; that they should not see with their eyes, nor understand with their heart, and be converted, and I should heal them. These things said Esaias, when he saw his glory, and spake of him.

This clearly indicates one author, not a collection of voices. Jesus and the apostles consistently treat Isaiah as a unified work, with no suggestion of multiple contributors. The Great Isaiah Scroll, discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls and dating to the 2nd century BC, is the oldest complete manuscript of Isaiah and shows no division at chapter 39. Instead, it flows seamlessly, as seen in the transition from chapter 39’s prophecy of exile to chapter 40’s promise of comfort.

Isaiah 39:5–8 warns Hezekiah of Babylon’s coming plunder, while 40:1–5 immediately offers solace: “Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God. Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem, and cry unto her, that her warfare is accomplished, that her iniquity is pardoned.” This continuity refutes the idea of an abrupt ending at chapter 39; the text naturally progresses from judgment to hope, setting the stage for John the Baptist and Christ’s coming. The notion that later chapters address only exilic audiences ignores the prophetic genre, which often spans multiple eras, including Christ’s time and beyond.

Modern “textual criticism” arguing for multiple authors relies heavily on subjective interpretations of style and tone, yet fails to account for the prophetic ability to speak to future contexts. For instance, Isaiah 53’s vivid depiction of the Suffering Servant, written as if already fulfilled, clearly points to Christ, not a figure confined to Babylonian exile. No ancient manuscript supports a divided Isaiah, and stopping at chapter 39 would be narratively jarring, lacking resolution.

Fragmenting Isaiah risks theological error, even heresy, by narrowing the scope of its Messianic prophecies. It suggests the Suffering Servant is a later, exilic invention rather than the enthroned Lord of chapter 6, breaking the continuity between Old and New Testaments. This undermines the divine inspiration of Scripture, implying human editors pieced together unrelated texts. Early Church Fathers like Jerome and Origen affirmed Isaiah’s unity, as did Jewish tradition. By quoting Isaiah as a cohesive work, Holy Scripture refutes such divisions. In a world quick to dissect sacred texts with human reasoning, Isaiah’s wholeness testifies to God’s timeless word, with Christ as the Alpha and Omega.

Isaiah 53:5

But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed.

Jeremiah (with Lamentations)¶

Jeremiah’s life was a testament to profound sorrow and unyielding faithfulness. Born around 650 BC in Anathoth, a priestly village near Jerusalem, he was called to prophesy as a young man in 626 BC, during King Josiah’s religious reforms aimed at purging idolatry. His ministry spanned over four decades, through the reigns of five kings -- Josiah, Jehoahaz, Jehoiakim, Jehoiachin, and Zedekiah -- ending with Jerusalem’s catastrophic fall to Babylon in 586 BC. Jeremiah’s message was deeply unpopular: he urged Judah to accept Babylonian rule as God’s judgment for their sins, earning accusations of treason. He endured relentless persecution -- beatings, imprisonment in stocks, confinement in a muddy cistern -- yet remained steadfast. After Jerusalem’s destruction, he stayed in Judah, counseling survivors, but was later taken against his will to Egypt, where tradition holds he was stoned to death by fellow exiles resentful of his warnings.

The Book of Jeremiah, compiled by his scribe Baruch, is a rich tapestry of oracles, biographical narratives, and personal confessions, arranged thematically rather than chronologically. It indicts Judah for breaking the covenant through idolatry (worshiping Baal and other gods), child sacrifice, and oppression of the poor, widows, and orphans. False prophets promised peace and prosperity, lulling the nation into complacency, but Jeremiah countered with stark warnings of exile as a divine purifying discipline. His imagery is vivid and haunting: a boiling pot tilting from the north (1:13) symbolizes Babylon’s invasion; a potter reshaping marred clay (18:1–6) illustrates God’s sovereignty to remake nations; a basket of rotten figs (24) represents Judah’s corrupt leaders. These metaphors made abstract truths palpable, searing God’s message into the people’s consciousness.

Jeremiah’s “confessions” reveal his inner turmoil, offering a raw glimpse into the prophet’s heart. He laments, “Cursed be the day wherein I was born” (20:14), anguished by rejection and the burden of his message, yet he finds sustenance in God’s word: “Thy words were found, and I did eat them; and thy word was unto me the joy and rejoicing of mine heart” (15:16). This tension -- despair paired with devotion -- humanizes Jeremiah, showing the personal cost of prophetic obedience. His vulnerability invites us to reflect: How do we bear the weight of truth in a world that often rejects it?

The book’s centerpiece is the promise of a new covenant: “I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts; and will be their God, and they shall be my people” (31:33). Unlike the old covenant, etched on stone tablets and broken by Israel’s unfaithfulness, this new covenant transforms hearts and forgives sins forever -- a promise fulfilled in Christ’s sacrifice, as Hebrews 8:7–13 affirms. This vision of inner renewal offers hope amid exile’s despair, showing that God’s mercy persists even in the darkest judgment. The Messianic hope is furthered in prophecies like the “righteous Branch” from David’s line (23:5–6), a king who will execute justice, pointing directly to Christ.

Lamentations, traditionally attributed to Jeremiah, consists of five acrostic poems mourning Jerusalem’s fall in 586 BC. The imagery is gut-wrenching: starving children cry in the streets, mothers resort to cannibalism, and the once-glorious city lies in ruins, personified as a desolate widow. The acrostic structure -- each verse beginning with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet -- imposes order on chaos, reflecting theological conviction that God remains sovereign. Amid this grief, a beacon of hope emerges: “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceaseth; his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning: great is thy faithfulness” (3:22–23). This blend of lament and trust underscores God’s enduring compassion, even when His people face the consequences of their sins.

Jeremiah’s life and words teach the high cost of prophetic faithfulness. Speaking truth often invites rejection, yet obedience aligns with God’s redemptive plan. His tears reveal God’s own sorrow over human sin, making prophecy deeply personal. In an era of easy optimism or “prosperity gospels,” Jeremiah’s suffering challenges us to embrace repentance as the path to true renewal. His new covenant promise prompts introspection: Is God’s law being written on our hearts, or do we cling to broken cisterns -- empty substitutes like wealth or self-reliance -- that hold no water?

Jeremiah 31:33

But this shall be the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel; After those days, saith the Lord, I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts; and will be their God, and they shall be my people.

Daniel¶

Daniel’s life bridges the courts of empires and the realm of divine vision, offering a testament to faithfulness under pressure. Taken captive as a noble youth from Judah in 605 BC, he served in Babylonian and later Persian courts until around 536 BC, rising to prominence through wisdom and integrity. His book, a blend of historical narratives and apocalyptic visions, spans the reigns of Nebuchadnezzar, Belshazzar, Darius, and Cyrus, showcasing God’s sovereignty over human powers.

The first half (chapters 1–6) recounts dramatic stories that highlight God’s protection. Daniel and his friends -- Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego -- refuse the king’s food to honor God’s law (1), demonstrating faithfulness in a pagan culture. They survive the fiery furnace (3) and Daniel the lions’ den (6), proving God’s power over earthly threats. Daniel interprets Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of a statue -- representing successive empires (Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, Rome) crushed by a divine stone (2) -- and Belshazzar’s ominous handwriting on the wall (5), foretelling Babylon’s fall.

The second half (7–12) unveils apocalyptic visions: four beasts from the sea (7), symbolizing empires; a ram and goat (8), depicting Persia and Greece; and the “seventy weeks” (9:24–27), a timeline pointing to the Messiah’s coming. The “Son of Man” receiving eternal dominion (7:13–14) becomes Jesus’ self-title (Matthew 26:64), linking Daniel’s visions to Christ’s kingdom. The promise of resurrection -- “many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame” (12:2) -- offers hope beyond temporal powers.

Daniel’s book emphasizes God’s control over history, the call to remain faithful in hostile cultures, and the assurance of resurrection. His ability to serve pagan kings without compromising faith models cultural engagement with integrity. In a world of clashing ideologies and powers, Daniel’s courage prompts us to ask: Where do we see God’s kingdom breaking through, and how do we stand firm without bowing to cultural pressures? His visions assure us that no empire outlasts God’s eternal rule, inspiring steadfastness in an uncertain world.

Daniel 7:13-14

I saw in the night visions, and, behold, one like the Son of man came with the clouds of heaven, and came to the Ancient of days, and they brought him near before him. And there was given him dominion, and glory, and a kingdom, that all people, nations, and languages, should serve him: his dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and his kingdom that which shall not be destroyed.

Ezekiel¶

Ezekiel’s prophetic ministry unfolded in the shadow of exile, a time of displacement and despair for Judah. Born around 622 BC to a priestly family, he was taken captive to Babylon in 597 BC at age 25, settling by the Chebar canal in Tel-abib. Called to prophesy at 30 -- the age he would have begun priestly service in the Temple -- his displacement added poignancy to his mission. From 593 to 571 BC, Ezekiel delivered God’s word through surreal visions and dramatic acts, speaking to exiles longing for home and hope.

The Book of Ezekiel opens with a breathtaking theophany: a chariot-throne borne by four living creatures (cherubim), each with four faces (man, lion, ox, eagle) and wings, surrounded by wheels within wheels, full of eyes, carrying God’s glory (chapter 1). This vision of divine mobility assured exiles that God was not confined to Jerusalem’s Temple but present even in Babylon. Ezekiel’s prophetic acts were vivid and shocking: eating a scroll inscribed with lamentations (3:1–3) to internalize God’s word; lying bound for 430 days (4:4–8) to symbolize Judah’s and Israel’s years of sin; shaving his head and burning, scattering, or hiding the hair (5:1–4) to depict Jerusalem’s fate. These performances made abstract truths unforgettable, embedding God’s message in the exiles’ minds.

A central theme is the departure of God’s glory from the corrupt Temple (10–11), signaling judgment for idolatry and injustice, but its promised return to a renewed Temple (43) offers hope of restoration. Ezekiel introduces a radical shift in theology: individual responsibility. He declares, “The soul that sinneth, it shall die” (18:4), moving away from collective punishment to personal accountability -- a transformative concept for his audience. This emphasis challenges us to consider our own actions, not just societal failures, as we stand before God.

Hope permeates Ezekiel’s message, even in exile’s darkness. He prophesies a “new heart” and “new spirit” (36:26), where God will remove stony hearts and give hearts of flesh, a promise fulfilled in the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost (Acts 2). The vision of dry bones reviving in a valley (37:1–14) vividly portrays Israel’s restoration and, by extension, humanity’s resurrection through Christ -- a powerful image of God’s life-giving power. The Messianic hope shines in chapter 34, where God as Good Shepherd gathers scattered sheep, a role Jesus claims (John 10:11). Ezekiel’s vision of a restored Temple (40–48) with a river flowing to heal the land (47:1–12) foreshadows the new creation in Revelation 22.

Ezekiel’s personal suffering -- his wife’s death as a sign to the exiles (24:15–18) -- underscores the sacrificial cost of prophecy. He was commanded not to mourn publicly, mirroring Israel’s stunned silence in judgment. This models obedience in adversity, teaching that God’s word demands embodiment, not just proclamation. Ezekiel’s ministry invites reflection: In our own “exile” -- whether personal alienation or societal chaos -- how do we seek God’s renewing Spirit? His visions challenge us to imagine: If God can breathe life into dry bones, what dead areas of our lives await His transformative touch? Ezekiel shows that even in the darkest moments, God’s presence moves, promising restoration to those who turn to Him.

Ezekiel 36:26

A new heart also will I give you, and a new spirit will I put within you: and I will take away the stony heart out of your flesh, and I will give you an heart of flesh.

Book of the Twelve¶

The Book of the Twelve, or Minor Prophets, comprises shorter yet powerful messages that address specific crises with poetic intensity. From the Assyrian threat to post-exilic rebuilding, these prophets -- Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi -- confront sin, call for repentance, and proclaim hope. Their brevity belies their depth; each book carries divine weight, challenging personal and societal failures while pointing to God’s redemptive plan. Their messages, often tied to historical moments, transcend time, urging us to examine our own faithfulness in a world prone to idolatry and injustice.

Hosea¶

Hosea ministered in northern Israel from around 755 to 715 BC, during a time of outward prosperity but inward moral decay under kings like Jeroboam II. God’s command to marry Gomer, a prostitute, was a living parable: her unfaithfulness mirrored Israel’s idolatry, chasing after Baal and other gods. Hosea’s redemption of Gomer, despite her betrayal, reflected God’s steadfast love for His covenant people, willing to restore even the wayward.

The book alternates between oracles of judgment -- calling Israel a faithless wife (2:2–13) -- and promises of restoration: “I will betroth thee unto me for ever; yea, I will betroth thee unto me in righteousness, and in judgment, and in lovingkindness” (2:19). Hosea’s Messianic vision, “After two days will he revive us: in the third day he will raise us up, and we shall live in his sight” (6:2), foreshadows Christ’s resurrection, a hope fulfilled on the third day (1 Corinthians 15:4).

Hosea’s life teaches the pain and power of faithful love. His willingness to redeem Gomer, despite personal cost, mirrors God’s pursuit of humanity. When we stray into our own “idolatries” -- whether materialism or self-centeredness -- Hosea’s message challenges us to ask: Does God’s persistent love humble us to return? His call to covenant faithfulness resonates, urging us to seek restoration through repentance.

Hosea 6:2

After two days will he revive us: in the third day he will raise us up, and we shall live in his sight.

Joel¶

Joel’s prophecy, dated possibly to the 9th century BC or post-exilic period, uses a devastating locust plague as a metaphor for divine judgment, likening it to an invading army signaling the “day of the Lord.” His call to repentance is urgent: “Rend your heart, and not your garments, and turn unto the Lord your God” (2:13). Joel promises restoration -- abundant harvests and spiritual renewal -- if the people return.

The book’s Messianic vision is profound: “I will pour out my spirit upon all flesh; and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy” (2:28), a prophecy fulfilled at Pentecost when Peter quoted it (Acts 2:16–21). Joel’s imagery of locusts and restoration speaks to cycles of destruction and renewal, applicable to any era.

Joel’s message teaches that crises -- whether natural disasters or personal trials -- are opportunities to turn to God. His assurance of the Spirit’s outpouring offers hope beyond judgment. In our world of environmental and social upheavals, Joel prompts us to consider: Do we see “locusts” as mere misfortunes, or as calls to repentance that open the door to renewal? His vision urges us to seek God’s transformative Spirit in the face of chaos.

Joel 2:28

And it shall come to pass afterward, that I will pour out my spirit upon all flesh; and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, your young men shall see visions.

Amos¶

Amos, a shepherd and fig farmer from Tekoa in Judah, prophesied to northern Israel around 760–750 BC, during Jeroboam II’s prosperous reign. Beneath the wealth lay corruption: the elite exploited the poor, perverted justice, and indulged in hollow religious rituals. Amos thundered against this hypocrisy: “I hate, I despise your feast days, and I will not smell in your solemn assemblies” (5:21). His vision of a plumb line (7:7–9) measured Israel’s righteousness, finding it wanting.

Amos’s oracles extend judgment to surrounding nations -- Damascus, Gaza, Tyre -- before zeroing in on Israel, showing God’s universal justice. Yet, hope emerges: “I will raise up the tabernacle of David that is fallen” (9:11), a Messianic promise of restoration quoted in Acts 15:16 to affirm Gentile inclusion.

Amos’s rustic voice teaches that true worship demands justice and righteousness. His call to “let judgment run down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream” (5:24) resonates in any society marked by inequality. In our affluent world, Amos challenges us to examine: Does our faith translate into action, or do we hide behind empty rituals? His message urges integrity, aligning worship with ethical living.

Amos 5:24

But let judgment run down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream.

Obadiah¶

Obadiah, likely writing around 586 BC after Jerusalem’s fall, delivers the shortest book in the Old Testament -- a single chapter condemning Edom for its betrayal. Descendants of Esau, Edomites gloated over brother Judah’s destruction by Babylon, even aiding the enemy. Obadiah declares, “As thou hast done, it shall be done unto thee” (1:15), promising Edom’s downfall for its pride and disloyalty.

The book’s climax envisions God’s kingdom: “The kingdom shall be the Lord’s” (1:21), a Messianic hope where justice prevails. Obadiah’s focus on brotherhood -- Edom as Esau to Judah’s Jacob -- underscores the sin of abandoning kin in crisis.

Obadiah’s message teaches that pride precedes destruction, and loyalty to God’s people is non-negotiable. In our polarized world, where rivalries and schadenfreude abound, Obadiah prompts us to ask: Do we gloat over others’ falls, or show solidarity? His brevity amplifies the warning: God judges those who betray His covenant community.

Obadiah 1:15

For the day of the Lord is near upon all the heathen: as thou hast done, it shall be done unto thee: thy reward shall return upon thine own head.

Jonah¶

Jonah’s story, set around 785–760 BC, is unique among the prophets for its narrative focus. Called to preach repentance to Nineveh, Assyria’s brutal capital, Jonah fled by ship, fearing or resenting God’s mercy toward enemies. Swallowed by a great fish, he prayed from its belly, repenting and vowing obedience. Nineveh, astonishingly, heeded his warning and repented, averting judgment. Jonah, however, sulked, angry at God’s compassion.

The book’s Messianic significance lies in the “sign of Jonah” -- three days in the fish foreshadowing Christ’s burial and resurrection (Matthew 12:40). Jonah’s reluctance highlights human prejudice against “outsiders,” contrasted with God’s universal love.

Jonah’s story teaches obedience to God’s call, even when it challenges biases. In a world divided by tribalism, Jonah challenges us to reflect: Who are our “Ninevehs” -- people or groups we’d rather not see redeemed? His narrative reveals God’s heart for all nations, pushing us to embrace His expansive mercy.

Jonah 2:9

But I will sacrifice unto thee with the voice of thanksgiving; I will pay that that I have vowed. Salvation is of the Lord.

Micah¶

Micah, active from 735 to 700 BC, prophesied to both Judah and Israel during a time of moral and social decay. A contemporary of Isaiah, he decried leaders who “judge for a bribe” and prophets who “divine for money” (3:11), exposing greed and corruption. His vision of peace -- nations beating swords into plowshares (4:3) -- offers hope amid judgment.

Micah’s Messianic prophecy is precise: “But thou, Bethlehem Ephratah, though thou be little among the thousands of Judah, yet out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel” (5:2), fulfilled in Christ’s birth (Matthew 2:6). His call to “do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God” (6:8) distills faith’s essence into lived ethics.

Micah’s message teaches that true devotion is practical, not ritualistic. In a world of systemic injustice, Micah urges us to consider: Does our faith shape our actions, or remain confined to words? His vision of peace challenges us to embody God’s kingdom through humility and justice.

Micah 6:8

He hath shewed thee, O man, what is good; and what doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?

Nahum¶

Nahum, writing between 663 and 612 BC, proclaimed the fall of Nineveh, Assyria’s capital, reversing Jonah’s earlier mercy due to the city’s relapse into cruelty. Where Jonah saw repentance, Nahum sees judgment: “The Lord is slow to anger, and great in power, and will not at all acquit the wicked” (1:3). His poetic imagery -- chariots rushing, shields red with blood -- vividly depicts Assyria’s collapse.

Nahum’s message offers comfort to Judah, oppressed by Assyrian tyranny: “The Lord is good, a strong hold in the day of trouble” (1:7). The “good tidings” of peace (1:15) align with Messianic hope (cf. Isaiah 52:7).

Nahum’s prophecy teaches that God’s justice, though delayed, is certain. In an age of oppressive systems, Nahum prompts us to reflect: Does the assurance of divine retribution offer solace, or challenge us to actively seek justice? His words remind us that evil’s reign is temporary, and God’s goodness prevails.

Nahum 1:7

The Lord is good, a strong hold in the day of trouble; and he knoweth them that trust in him.

Habakkuk¶

Habakkuk, active around 612–589 BC, wrestled with a theological dilemma: Why would God use the wicked Babylonians to punish Judah? His book is a dialogue with God, blending questions, visions, and a concluding hymn. God’s response: “The vision is yet for an appointed time… the just shall live by his faith” (2:3–4), a verse pivotal in Romans 1:17.

Habakkuk’s faith grows, culminating in a psalm of trust: “Yet I will rejoice in the Lord, I will joy in the God of my salvation” (3:18), even if crops fail. This shift from doubt to worship models honest engagement with God.

Habakkuk’s dialogue teaches that questioning God, when rooted in faith, leads to deeper trust. When life’s injustices perplex us, Habakkuk challenges us to ask: Can we find joy in God amid unanswered questions? His resilience inspires steadfastness in uncertainty.

Habakkuk 2:4

Behold, his soul which is lifted up is not upright in him: but the just shall live by his faith.

Zephaniah¶

Zephaniah, prophesying around 640–609 BC under King Josiah, warned of the “day of the Lord” as universal judgment sweeping Judah and nations for idolatry and pride. Yet, a humble remnant would survive, restored to worship with a “pure language” (3:9).

His Messianic vision is intimate: “The Lord thy God in the midst of thee is mighty; he will save, he will rejoice over thee with joy” (3:17), portraying God singing over His people. This tenderness amid wrath highlights divine love.

Zephaniah’s message teaches humility as salvation’s path. In a world of hubris, Zephaniah prompts us to reflect: Does God’s joyful presence inspire us to seek simplicity and trust? His remnant hope encourages perseverance through judgment.

Zephaniah 3:17

The Lord thy God in the midst of thee is mighty; he will save, he will rejoice over thee with joy; he will rest in his love, he will joy over thee with singing.

Haggai¶

Haggai prophesied in 520 BC, after the Babylonian exile, urging returned Jews to rebuild the Temple neglected amid personal pursuits. His brief book -- only two chapters -- delivers four messages, chastising apathy: “Is it time for you to dwell in your ceiled houses, and this house lie waste?” (1:4). Obedience brings promise: “The glory of this latter house shall be greater than of the former” (2:9).

Haggai’s Messianic hope, the “Desire of all nations” (2:7), points to Christ filling the Temple with divine presence. His call to prioritize God’s work resonates in any age of distraction.

Haggai’s prophecy teaches that obedience unlocks blessing. In our busy lives, Haggai challenges us to ask: What “temples” -- spiritual or communal -- do we neglect for personal gain? His urgency spurs us to realign priorities with God’s kingdom.

Haggai 2:9

The glory of this latter house shall be greater than of the former, saith the Lord of hosts: and in this place will I give peace, saith the Lord of hosts.

Zechariah¶

Zechariah, prophesying alongside Haggai in 520–518 BC, encouraged Temple rebuilding through eight symbolic visions: a horseman among myrtles, a measuring line, a cleansed high priest. These assure purification and restoration, with Jerusalem as God’s dwelling.

Messianic prophecies abound: the pierced one mourned (12:10; John 19:37), the humble King riding a donkey (9:9; Matthew 21:5). Zechariah’s imagery -- Branch, Cornerstone -- points to Christ’s priesthood and kingship.

Zechariah’s visions teach that God rebuilds from ruins. In our broken world, Zechariah prompts us to consider: Do we see God’s visions of renewal fueling our efforts? His hope inspires action amid despair.

Zechariah 9:9

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem: behold, thy King cometh unto thee: he is just, and having salvation; lowly, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt the foal of an ass.

Malachi¶

Malachi, writing around 430 BC after the Temple’s restoration, rebuked post-exilic Judah for complacency: corrupt priests offered blemished sacrifices, husbands betrayed wives through divorce. His name, meaning “my messenger,” underscores his role as the final OT prophet, bridging to the New Testament.

Malachi’s Messianic promises include the “messenger of the covenant” (3:1), fulfilled in John the Baptist, and the “Sun of righteousness” rising with healing (4:2). His closing call for Elijah’s return (4:5–6) heightens anticipation for Christ.

Malachi’s message teaches pure worship’s importance. As the OT’s last voice, Malachi challenges us to ask: Does his warning against apathy stir us to prepare for Christ’s coming? His words leave us longing for fulfillment.

Malachi 4:5-6

Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord: And he shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the earth with a curse.

Fulfillment and Legacy¶

The Old Testament prophets form a unified chorus pointing to Christ. From Isaiah’s Suffering Servant to Micah’s Bethlehem Ruler, their visions find fulfillment in Jesus’ birth, ministry, death, and resurrection. As He explained on the Emmaus road, “beginning at Moses and all the prophets, he expounded unto them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself” (Luke 24:27). This convergence underscores the divine inspiration of their words, weaving a narrative across centuries.

Their legacy is enduring. These prophets modeled courage, speaking truth to power despite persecution, blending lament over sin with hope in redemption. In a world of ancient polytheism and empire, they proclaimed one God and ethical monotheism, shaping Judaism, Christianity, and Western morality. Today, they counter relativism, affirming absolute standards and God’s sovereignty over history. Their calls for justice, faith, and repentance remain urgent.

If the prophets judged ancient nations for idolatry and injustice, what would they say to our world of materialism, division, and spiritual drift? Their enduring call is to turn to Christ, the fulfillment of all prophecy, who offers eternal life through metanoia. For deeper insight, explore patristic commentaries like Origen’s on Jonah or Jerome’s on Isaiah, which reveal how early Christians saw Christ woven through these texts.

Luke 24:27

And beginning at Moses and all the prophets, he expounded unto them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself.